Explosion in The Narrows: The 1917 Halifax Harbour Explosion

On the morning of December 6th, 1917, the steamship Mont-Blanc, inbound from the Atlantic with war material for France, entered the Halifax Harbour Narrows. The Norwegian ship Imo left Bedford Basin, outbound for New York to load supplies for occupied Belgium. In homes, schools, and factories lining the shores, people started a new day in a busy wartime port. When Imo crossed The Narrows and struck Mont-Blanc’s bow, worlds collided.

Imo aground and under guard on the Dartmouth shore CREDIT: MP 207.1.184/270

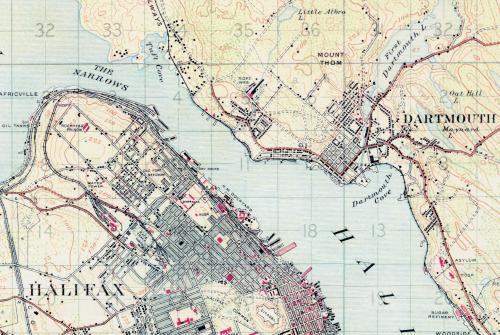

Kepe’kek: At the Narrows

In Mi’kma’ki—the present and ancestral territory of the Mi’kmaw people—Kjipuktuk (Halifax Harbour) is one feature of an enduring indigenous landscape comprising much of northeastern North America. The area of harbour where Imo struck Mont-Blanc was known by Mi’kmaw people as Kepe'kek, “at the Narrows.”

“Halifax, N.W.”, 1918 [detail], showing the Halifax Harbour Narrows. CREDIT: Nova Scotia Archives Map Collection: V5 1: 31 680. 133a

Canada and Global War

Halifax is North America’s closest large port to Europe. The Narrows’ shoreline was shaped by rail lines stretching from shipping terminals into the continental interior. Residents in the communities of Richmond and Africville depended on the railway, the factories, the waterfront.

The mortuary effects of Matteo Cicione, an Italian longshoreman killed in the blast.

Troop train at Pier No. 2, Halifax CREDIT: Nova Scotia Archives, Helen Creighton, Album 11 No. 32

The city’s rail and shipping facilities were quickly integrated into the nation’s war effort. Hundreds of thousands of service personnel departed from Deepwater Terminals for the battlefields of Europe. Halifax was as fully engaged in the war as any North American city could be.

Collision in The Narrows

Mont-Blanc’s main cargo was bulk high explosives. When barrels of petrochemical on deck triggered the blast, the ship was transformed into a three-kiloton bomb in a busy modern port.

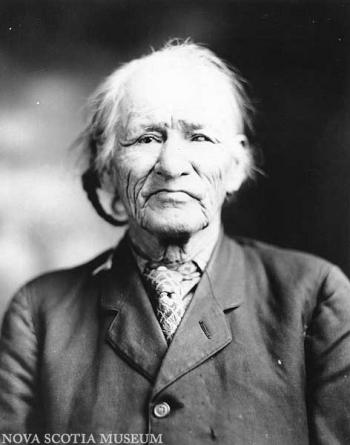

Mi’kmaw elder Jerry Lonecloud (Mi’kmaq Slme’n Laksi, baptised Germain Bartlett Alexis) fought to secure lands for the residents of Turtle Grove. Two of his children—Hannah and Rosie—were killed by the blast. Nova Scotia Museum History Collection, 29.4

A roiling cloud of hot gas rose high above the blast. Chunks and shards of the ship fell across an eight-kilometre range. Vaporized fuel and chemicals from the explosion fell as rain, coating people and wreckage with an oily film. Richmond and the Mi’kmaw community of Turtle Grove were struck by the full force of the blast. More than 1700 people were killed by the explosion and its after-effects. At least 9000 were injured and many more were made homeless.

Mortuary effects from some of those killed in the explosion.

Fragments of the ship displayed at the Maritime Museum.

Ruins of shipping piers at Richmond after the Explosion. MP207.1.184/47, Charles A. Vaughan Collection

The Explosion immediately disrupted communications linking North America, Nova Scotia, and the world overseas. Roadways, telegraph and telephone lines, submarine cables were disrupted by the blast. Rail links to the piers, and many of the piers themselves, were destroyed.

Richmond Railway Yards after the Explosion CREDIT: MP207.1.184/47, Charles A. Vaughan Collection

Rescue and Relief

People in the districts immediately surrounding the devastated area provided the first relief. Many first responders were soldiers and sailors from Canadian, British, and United States’ ships in port.

Queen’s University Archives, Queen’s Picture Collection, 96891

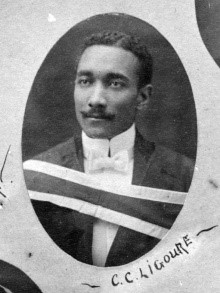

Trinidad-born Dr. Clement Courtenay Ligoure treated survivors from the ruined factories, railyards, and rehomesof the city’s north end for weeks after the blast. Denied privileges in the city’s medical facilities because of his race, he opened a private hospital. Dr. Ligoiure was a well-known public figure, recruiting for the No. 2 Construction Battalion and editing The Atlantic Advocate, one of Canada’s first magazines produced by and for people of colour.

Six relief trains arrived from Nova Scotia and New Brunswick on the day of the blast. As news of the Halifax Harbour Explosion spread, people all over the world acted to relieve the mass suffering it had caused.

Commemorating Disaster

In 1994, the museum opened “Halifax Wrecked”, a permanent exhibit devoted to the Explosion. An updated version of this exhibit, “Explosion in The Narrows”, opened in 2019, aims to broaden public understanding of the many and diverse communities—Mi’kmaw, African-Nova Scotian, recent migrant, military—affected by these events.

Fort Needham Memorial Bell Tower. Christian Laforce

Research Links

Book of Remembrance online database at the Nova Scotia Archives

A Vision of Regeneration

Virtual exhibit about the explosion and reconstruction by the Nova Scotia Archives and Records Management

HRM Municipal Archives historical sources on the Halifax Explosion

Detailed documentation of Halifax and Dartmouth's response to the Explosion provided through links to digitized copies of the original historical records.

Library and Archives Canada thematic guide to the Halifax Explosion

This guide consists of specific archival references and a selected bibliography relating to the Halifax Explosion of 1917.

Historica Canada Heritage Minutes: Halifax Explosion

Train dispatcher Vincent Coleman sacrifices his own life to save a train from the Halifax Explosion.

RUSI(NS) Military Response to the Halifax Explosion

An overview of the crucial and underappreciated efforts of Army and Navy personnel in the aftermath of the Explosion.

Pilot Francis Mackey and the Halifax Explosion

Pilot Francis Mackey was one of the individuals who were unfairly blamed for the disaster. His side of the story has never been told.”

CBC Halifax Explosion Web Site

A large and interactive site on the explosion and its effect on the people of Halifax.